In a new article recently published online by the Journal of European Social Policy, DEEPEN team member Natascha van der Zwan (Leiden University) and Ville-Pekka Sorsa (University of Helsinki) argue against expert and scholarly understandings of pension sustainability as affordability and adequacy. Instead, they shift focus to political sustainability: policymakers’ ability to maintain consensus around pension scheme parameters and avert pressures for change. The key question is: do policymakers have the willingness and the ability to sustain the pension scheme?

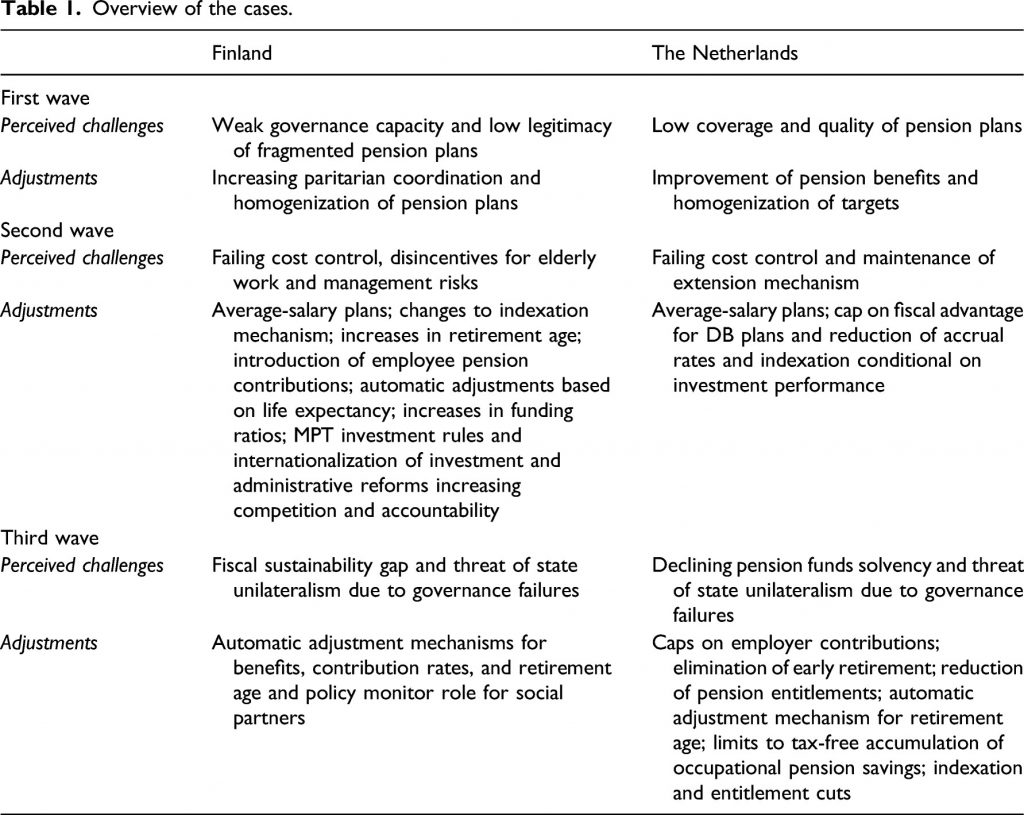

To answer this question, Van der Zwan and Sorsa compare the cases of Finland and the Netherlands: two mature three-pillar pension regimes characterized by the long-term survival of large-scale, funded and collective DB pensions. In both countries, they identify three historical waves of pension reform (see table 1 below). Each of the three waves is characterized by different political concerns over the long-term sustainability of collective DB pensions. For instance: during the first wave of pension reform, which took place in the formative years of both pension systems, policymakers were concerned about low coverage of collective DB pensions, which threatened the survival of the system. In later waves, sustainability concerns centered on the fiscal sustainability of the pension system (Finland) and low solvency of pension funds (Netherlands).

Table 1: Overview of the cases

Crucially, policymakers in both countries responded to these concerns by making parametric changes to collective pensions. Van der Zwan and Sorsa find that, in the two cases, nine types of pension scheme parameters have been (re-)negotiated (see Table 2). For instance, sustainability concerns in the Netherlands during the late 1990s directly informed parametric changes, such as changes to the accrual rates (from final to average-salary DB) and the elimination of automatic adjustments of pension rights to wage or price increases (conditional indexation). Both adjustments successfully sustained the DB nature of collective pensions and averted a paradigmatic switch to DC pensions.

The comparison highlights the importance of governance practices for the possibility of adjustment. Both countries are characterized by long-standing traditions of corporatism in the pension system. Policymakers’ willingness to sustain stemmed from their perception of the key collective pension schemes as important power resources. The social partners did not only consider the schemes crucial for the legitimacy of corporatist governance, but also accepted compromises to improve or maintain their own status in pension governance. Governments of the two states, meanwhile, also considered collective pensions essential, often for economic reasons.

Table 2: Pension parameters

| Parameter | |

| Benefits | Pension salary |

| Accrual rate | |

| Indexation of accrued pension rights | |

| Eligibility | Years of employment |

| Additional conditions for retirement | |

| Financing | Contributions by employers and/or employees |

| Investment policy and management | |

| Investment regulations | |

| Governance | Management and administration of pension plans |

The authors draw two conclusions from their study. First, even perceived unsustainable features of pensions can be adjusted to changing circumstances, as long as policymakers and stakeholders regard all pension scheme parameters as negotiable. These findings inform the second conclusion: not just policy design, but also governance considerations are necessary for sustaining pensions. If stable political coalitions are central to the political sustainability of social policies, then governance interests and concerns need to be more seriously taken into account if policymakers wish to build sustainable pension schemes.

Even though the focus is on pensions, the authors’ findings are relevant for the wider scholarship of social policy. Sustainability offers a useful concept for understanding the long-term prevalence of social policies and institutions like pension schemes. However, without explaining why different actors maintain and renew some social policies and welfare institutions but not others, sustainability research will have little to say about the actual longevity of policies and institutions. Van der Zwan and Sorsa’s findings can be summarized as the following maxim on sustainability: the capacity to sustain a welfare scheme is primary to any particular conception of sustainability based on a narrow set of policy indicators.

This has become apparent in the Netherlands, where a fourth wave of adjustment has moved the policy paradigm towards CDC pensions. The deviatingtrajectory of the Netherlands since the 2010s shows how the very process of sustaining can also disrupt existing pension policy. When cracks emerged in the consensus between the social partners, the state was able to increase its influence. State interventions either fixed some parameters or led social partners to consider certain parameters as non-negotiable. Once social partners become unwilling to negotiate particular pension parameters (the contribution rate for employers; the retirement age for unions), possibilities for parametric adjustments are closed off. The Dutch social partners choose to maintain collective administration of occupational pensions at the expense of the DB nature of the pension contract.

This leaves readers with an important recommendation for future research on welfare sustainability: rather than conceptualizing sustainability as a ‘tick-box’ exercise of available policy instruments external to the policy process, scholars of social policy should consider how institutional capacities and governance practice shape the complex ways in which policymakers create sustainable welfare states.

Read the entire article here.